Around 11:30 a.m. on February 9, 1992, two nervous men arrived at the Cage aux sports on Boulevard de la Concorde in Laval. They know they screwed up. They are accountable. They received $8,000 from two kingpins for a shipment of 125 stolen washers and dryers. But they were arrested by the police four days earlier. All stock has been seized. They burned the money. And they are “broken like a nail”.

This Monday noon, it’s time for explanations.

The two men are called Gérard Bourgade and Claude Riendeau. Bourgade is a seemingly uneventful trucker who supplements his pay by importing cocaine on his trips to the United States.

Claude Riendeau, on the other hand, is an ex-cop turned armed robber, loan shark, coke trafficker and arms “retailer”, as he likes to put it modestly.

The men with whom Bourgade and Riendeau have an appointment do not have the reputation of being “the forgiving insurer”, nor of the followers of the “third chance at credit”.

They are Denis Lemieux, a South Shore drug lord, and his loyal lieutenant, François Leblanc.

If the rendezvous is in Laval, it’s because Lemieux owns a “Cantel” branch selling cell phones in the same complex as the Cage aux sports. Trade serves as a legal screen for its true activities. Officially, Leblanc is his employee. What are these two drug dealers doing in the stolen van business? Quick money, and for much less danger than dope. Lemieux is the one who has the contacts to sell the stolen tractor-trailers. The business is very lucrative. A single stolen trailer can bring in $50,000, $100,000, or $250,000 at the time, depending on the stolen goods.

Thirty years later, one wonders if this informant was not Riendeau himself. This would not have been his first betrayal in the “middle”. He had been an informer in 1987 in the trial of his robber accomplice convicted of the murder of a policeman. And when he is again an informer, at the trial of Daniel Jolivet, we will learn that he was a “coded informer” to the Montreal police. The police said it was simply for his work as an informer in 1987. But doubt still hangs. Especially since when they seized the appliance trailer, Riendeau was quickly released by the anti-gang police, without being charged – he was however driving Bourgade’s car, without a license, and on release. conditional.

According to Bourgade and Riendeau, the meeting at the Cage aux sports went wonderfully. Both creditors were understanding: bad luck is never safe, right? Lemieux and Leblanc didn’t even set a deadline for repaying the $8,000, Riendeau said.

Little did Lemieux and Leblanc know that the duo had played a double game by selling the trailer a second time, this time for $12,000 to another buyer, as Lemieux and Leblanc were slow to take delivery of the goods.

But did they have any doubts about this Riendeau, who had been introduced to them a few months earlier by Jolivet? An ex-cop sniffing his profits… And then, how did the anti-gang know? Never good for business, that. Were these two reliable?

We have already seen Jolivet’s name in the newspapers. In 1990, he had been locked up for harboring nine luxury cars, three yachts, etc. A bargain of $375,000 at the time.

Jolivet knew St-Pierre in 1992. He is a guy from the Pointe-Saint-Charles district, like him, and he has worked in the criminal world too. But it was rather with Riendeau that he was hitting. They had in common a taste for gunpowder – Jolivet always had a horror of alcohol and cocaine.

It is from this precise moment, when the two new guests show up, that everything changes, around noon, this November 9, in this restaurant in Laval.

Let’s go back to the scene. They are six. There are Lemieux and Leblanc, the bosses who finance coups. There is Bourgade and Riendeau, who have just had their stolen goods stolen by the police, already paid for by the bosses. And there is Jolivet and St-Pierre.

Version number 1, according to Jolivet.

Boss Lemieux ordered the two badass thieves (Riendeau and Bourgade) to pay him back before midnight.

Riendeau said he had a plan: to steal a seafood “van” destined for Red Lobster.

Leblanc was going to provide a weapon.

When he wants to become an informer in 1994, St-Pierre will confirm this version of the meeting at La Cage.

Riendeau and Bourgade are hot. They have 12 hours to pay their debt. They follow in their car Jolivet and St-Pierre, who stop on rue d’Iberville. Jolivet motions them to wait. He enters an apartment (an arms cache controlled by Leblanc) and comes out with a paper bag containing a machine gun, which he places in Riendeau’s car, at Bourgade’s feet.

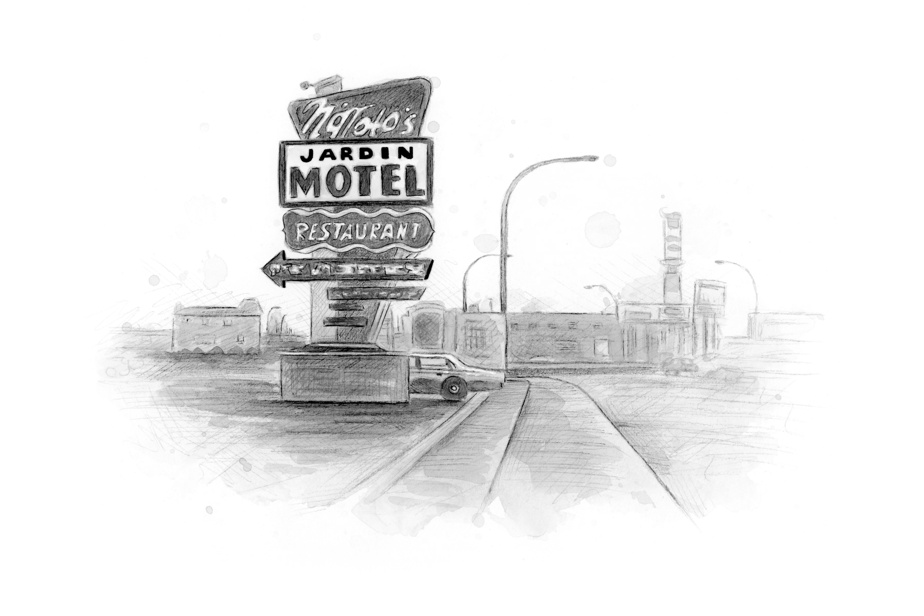

The four then go to the not-so-posh Motel Nittolo, a bandit hideout in NDG.

Still according to Jolivet, one must first try the rifle loaned to Riendeau, and two others that Leblanc gave him for sale. Bullets in magazines tend to get stuck. Riendeau, an ex-cop who has sold guns before (in addition to using them for hold-ups), understands that you have to adjust the “lips” of the magazines with a pair of pliers. Guys pull up the bedspread. Jolivet and Riendeau fire shots muffled by the silencer into the mattress, just to test the magazines. The projectiles found by the police under the bed (a dozen) show that all the rounds were fired with a single weapon, as Jolivet said: we were only testing the three magazines adjusted by Riendeau.

Everything is working. Everything’s good.

The four can relax. Jolivet fetches coke in his truck for the other three, and hash for himself. St-Pierre then calls Leblanc for a kilo of coke, then a second that he claims to sell in the evening for $34,000 each.

If Riendeau and Bourgade can sell one, they will be able to erase their debt.

Riendeau and Bourgade tell a completely different story.

According to them, everything was very cool with Lemieux and Leblanc. There was no plan to pay their debt. On the other hand, an allusion to an old cause of Jolivet had made Leblanc believe that Jolivet had betrayed a secret on a settling of accounts.

According to Riendeau, Jolivet became paranoid and decided on the spot to kill Lemieux and Leblanc before going through it himself – in addition to robbing them. Riendeau and Bourgade say that Jolivet was fired up at the motel, talked about killing, and even had an erection while shooting into the mattress. Both told police they were scared for their own lives because he looked crazy.

The two duos (Jolivet/St-Pierre and Riendeau/Bourgade) left the motel around 5:30 p.m. St-Pierre, with two kilos of coke for sale.

What happened the rest of the evening? And the next night, who claimed the lives of Lemieux, Leblanc, Katherine Morin and Nathalie Beauregard?

It is 8 a.m. on Tuesday, November 10, 1992. Except for the killers, no one knows that four people were shot dead overnight in a condo complex in Brossard.

Claude Riendeau calls investigator Daniel Kerouac, from the Montreal police anti-gang squad, on his pager. It was this policeman, with his partner Robert Octeau, who arrested him five days earlier, in the case of the “van” of household appliances.

Riendeau had been released without charge, strangely, and had received police officer Daniel Kerouac’s business card as a gift. This onion treatment for a career criminal caught in the act of violating his parole is very similar to the treatment of a police informer.

On the telephone, Riendeau informed the policeman.

“Note these names carefully: Denis Lemieux and François Leblanc,” said Riendeau. He adds that he is going to have lunch with Daniel Jolivet in a restaurant-counter in Pointe-Saint-Charles.

Strange message, for a man who does not know what happened during the night, and who supposedly went to bed quietly at 11 p.m. in the marital bed, in Saint-Hyacinthe.

According to his version, it was because he had been worried by the events of the day before: Jolivet trying a gun in the motel mattress, talking about murdering Lemieux and Leblanc…

For Daniel Jolivet, the motivation of this ex-cop is much more twisted: he prepares the ground. He is sowing in the heads of the police the first seeds to accuse Daniel Jolivet of the murders he himself committed.

Riendeau says that Jolivet himself called him to meet him for lunch at the Barabé restaurant. Telephone records show that it was Riendeau who called Jolivet that morning.

Also according to Riendeau, it was during this crucial lunch that Jolivet told him that his debt of $8,000 was wiped out, as he had murdered Lemieux and Leblanc during the night.

Riendeau, who is supposed to be terrified by this account, does not immediately go to the police. In fact, he leaves to join Gérard Bourgade and celebrates with him. They drink and “sniff” all afternoon.

It was only at 6 p.m. that Claude Riendeau met the police, in the parking lot of the Bifthèque restaurant, along Highway 20, on the South Shore.

To the two policemen, he tells the story of the carnage as Jolivet would have confessed to him at lunch.

According to these supposed confessions, Jolivet went at the end of the evening the day before to Leblanc, in Brossard. He had failed to sell the coke and Leblanc, furious, demanded a fee. Indeed, in Riendeau’s version, it was Jolivet who had to redeem himself by selling the coke, and not him.

Jolivet would then have pretended to return to his truck to look for the money owed, and would have returned with his machine gun, accompanied by St-Pierre. Back in the condo, that’s where he allegedly shot Leblanc, Lemieux, two other men and the two young women. Because in this first version, Riendeau says that Jolivet confessed to him not four, but six murders.

The police are impressed by this story of extreme violence. They call the Sûreté du Québec at 7:30 p.m. to report this possible sextuple assassination in Brossard. The SQ has just learned of the discovery of four dead bodies in Brossard.

As soon as the bodies are discovered in Brossard, the police hold Jolivet as a suspect thanks to the informer Riendeau. But that’s all she has: the word of a very dubious guy.

Jolivet and St-Pierre are quickly tapped. Microphones are installed in Jolivet’s truck. A recording device is even installed on Riendeau, to capture confessions from Jolivet. They are spun day and night.

All of this does nothing.

It’s all about the informer and evidence of movement based on cellphones.

Daniel Jolivet did not testify in his defense. His lawyer Ronnie MacDonald reminded him of his criminal record and explained an old principle from the big “book” of defense attorneys when the client is a habitual criminal: “If the jury has a choice to believe the Crown Bandit [ Riendeau] or the defense bandit [Jolivet], who do you think they’re going to believe? »

Jolivet was found guilty.

Four years later, the Quebec Court of Appeal, two judges to one, agreed with him on one point: the judge should have allowed his lawyer to point out to the jury the absence, never explained, of the witness Gérard Bourgade. The Crown had however told the jury that this witness would corroborate the testimony of the informer Claude Riendeau. A new trial is ordered.

But, writes Judge Ian Binnie, “there is no reasonable possibility that the verdict would have been different had the trial judge not made the error.”

The guilty verdict is restored. Jolivet has exhausted all his remedies.

All ? Not quite. He has one last card to play.